Building a Pipelined ML Product? Start Breadth-first

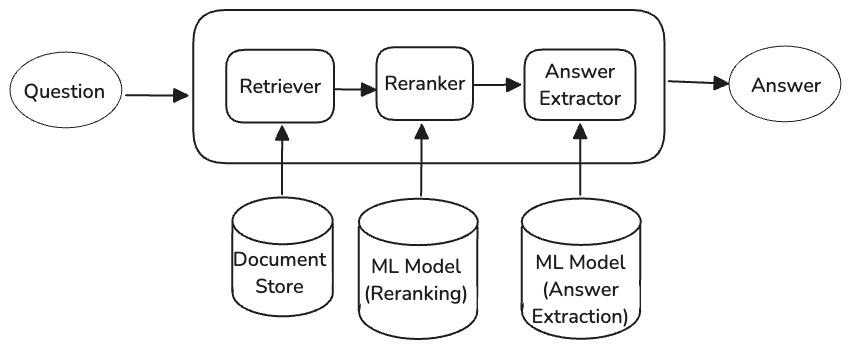

Search and natural language understanding systems are inherently pipelined. Figure 1 below shows an example of such a pipelined system, an extractive question answering system. The system takes a user question a produces an answer based on a given document collection.

Figure 1: Pipeline for an extractive question answering system.

One can take a breadth-first or a depth-first approach when building such systems. In a breadth-first approach you focus on building a working version of the end-to-end system as fast as possible and iterating on that. In a depth-first approach, you take the pipeline architecture, and you build and evaluate one component at a time. In this note I advocate for taking a breadth-first approach, especially during early stages of development.

There are three reasons why I advocate for a breadth-first approach, at least early on:

- Anytime approach to product building

- Error dynamics in a pipeline

- Perfection in any one stage might not be needed

Anytime Approach to Product Building

“Anytime approach” is inspired by the concept of an anytime algorithm (aka interruptible algorithm), which is one “that can return a valid solution to a problem even if it is interrupted before it ends. The algorithm is expected to find better and better solutions the longer it keeps running.”. When building a product, you should have something that is demonstrably getting better over time.

When building a product, your ultimate goal is typically to have something useful out as soon as possible, get feedback on that, and iterate. What is “useful” is often a function of time: a demo, a prototype, a proof-of-concept, an MVP, a mature product, etc. Feedback can come from colleagues, managers, investors, testers, customers, etc.

The reality of life is that people around you need to see progress through something concrete (i) to understand the current status, (ii) give feedback, (iii) make plans and (iv) for their own peace of mind. Consider the following scenario: you’re tasked with building a QA system of the type described at the top of this note. A few months pass, a (senior) manager ‘interrupts’ you and ask for a status update where they’re told “we’re almost done with perfecting first-stage retrieval”. The first two questions will probably be: “what impact will this have on the larger system?” and “can I play with a prototype?”.

To be clear, no real progress is possible without spending enough time on uninterrupted, focused depth-first work. Also, no real progress is possible without lots of failures if you’re doing something interesting/challenging. The message here is that starting breadth-first allows you to show something useful, even if imperfect, early on. It also allows you to justify any depth-first investments by re-integrating their outcomes into the end-to-end system you built early on.

For more on this, see:

- On teams, hiding is considered harmful

- Hiding Considered Harmful, from the book Software Engineering at Google: How to Work Well on Teams

Error Dynamics in a Pipeline

Later Stages can Fix Earlier Ones

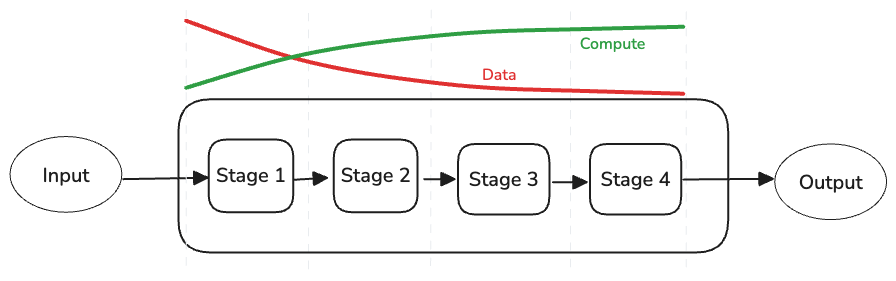

You almost never need any single component in a pipeline to be perfect. It is almost never possible anyway. Pipelines are often built around the following tradeoff: as you move from one stage of a pipeline to the next, you apply more compute power to smaller amounts of data. This often means that later parts of the pipeline are able to make up for any shortcomings in earlier ones.

Figure 2: Amount of data vs. amount of compute expended in a typical pipeline.

In the context of search systems, the classical example of the above is retrieval and re-ranking in an search pipeline. The retrieval stage takes a query and picks the best few hundred documents among thousands to millions of documents. A re-ranker then takes the few hundred retrieved documents and applies more computationally demanding algorithms (e.g. LTR, cross-encoders) to re-order these and pick the best 10-100. One can get easily fixated on getting the perfect retrieval stage. This is often not necessary as long as you can guarantee high-recall – which comes at the cost of low precision.

Prioritise Finding the Bottleneck(s)

Conversely, if later stages of the pipeline have major deficiencies, then making earlier ones perfect has no value and is wasted effort. Take the question answering pipeline in Figure 1: you might spend a month building an almost perfect retriever and another month building the perfect re-ranker. If your answer extractor struggles even when presented with the perfect document (i.e. idealised retrieval and re-ranker), that’s the limit to your pipeline’s overall performance. If you could go depth-first on one stage, it probably should have been the answer extractor.

Stages are not Independent

If you have enough people, you could distribute the work and go depth first on all stages from the beginning. What problems a given stage needs to solve is typically a function of what problems other stages create or solve. Other stages here refers to both previous and subsequent stages.

When to Go Depth-first?

First, go depth-first on what? In a pipelined system, you can typically go depth-first on: (i) a specific stage or (ii) the architecture of the pipeline.

As you’re building the first iteration of your pipelined system, you’ve hopefully been working on evaluating it. Take these evaluation results, one evaluation example at a time, and perform an error analysis to develop an understanding of why some work and some don’t. Trace errors to specific parts of the pipeline. Develop an understanding of what changes to the pipeline are likely to have maximum pay-off and prioritise going depth-first into these.

Going depth first on a specific stage typically involves reconsidering how it is implemented, which data it has access to, the models it uses, and how it is configured. It also involves developing a way to evaluate the stage independently.

When you start, you have to pick some architecture that you hypothesise will do a reasonable job. Once you have an end-to-end system and you analyse it, you might realise that you need to change the architecture. Some stages might be unnecessary or the cost they introduce is not worth the value they provide. There might be a need to introduce extra stages. There might even be a need to create multiple pipelines, each of which can handle a subset of the intended inputs.

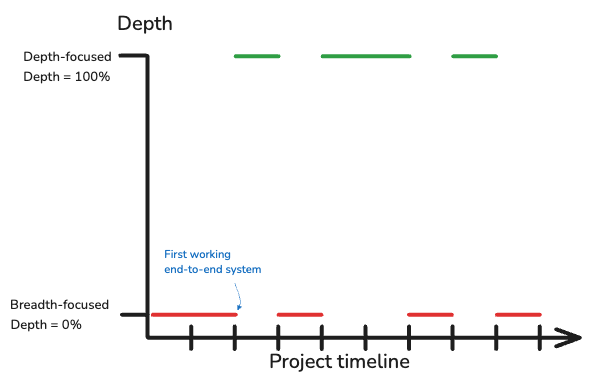

Make sure you’re regularly evaluating how any changes to a stage affect end-user evaluation – that’s what ultimately matter, see Figure 3. Dive deep, but remember to keep track of the big picture at the surface.

Figure 3: Iterating between breadth and depth.